Beckett: Naturally absurd in London

Happy Days – Young Vic, until 08 March 2014

Not I/ Footfalls / Rockaby – Duchess Theatre, until 15 February 2014

One tends to approach a Samuel Beckett play the sane way one would a wheatgrass smoothie or a quick dip in the English Channel, knowing that whilst not necessarily being enjoyable it is definitely something that should be undertaken. Certainly from the near full houses at the Duchess Theatre and the Young Vic it would seem that Beckett’s forbidding reputation is doing little to dissuade people from going to see his plays. Perhaps watching as most of Somerset disappears under water has done wonders for people’s sense of the absurd?

Whatever the reason, London is currently home to two major Beckett revivals; the Duchess Theatre, carving itself a niche in serious drama following their decision to host the hugely successful Chichester production of Arturo Ui, has transferred Not I from the Royal Court and paired it with two other late Beckett monologues, Footfalls and Rockaby.

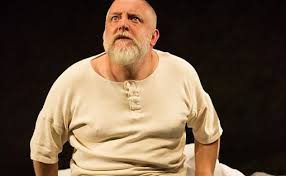

Not to be outdone the Young Vic has staged one of Beckett’s greatest works, Happy Days. Written in 1961 it came during a ten year stretch that also saw the production of Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Krapp’s Last Tape, as well as the novels, Malone Dies and The Unnameable. Comparatively young, at 63, compared to recent winners, the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969 must by then have been mere formality.

Watching both productions in the space of three days it is impossible not to become immersed into Beckett’s singular vision and begin to understand themes that, viewed in isolation, can seem elusive. It is common to talk about how ‘nothing happens’ in his plays but viewing the four works in close succession it is possible to see what Beckett intends through this effect.

In the trilogy at the Duchess Theatre, we see the increasing minimalism of his later work, which seeks to pare theatre back to its most fundamental elements: action, voice, reaction, and that probably reaches its apogee in Not I – a work that is part-theatre, part-performance art and part-tone poem and in which ‘nothing happens’ at a furious rate.

In Not I, the actor has become the literal mouthpiece for Beckett’s vision, in Footfalls every pace is prescribed before the actor steps onto stage and in Rockaby the actor can only react to what is offstage, they do not even control the rocking of the chair. Put together as one piece we, the audience, are left with an overwhelming sense of the lack of agency in the actor which seems to parallel the three characters inability to exert any sort of control over their environment.

In Not I, the actor has become the literal mouthpiece for Beckett’s vision, in Footfalls every pace is prescribed before the actor steps onto stage and in Rockaby the actor can only react to what is offstage, they do not even control the rocking of the chair. Put together as one piece we, the audience, are left with an overwhelming sense of the lack of agency in the actor which seems to parallel the three characters inability to exert any sort of control over their environment.

It is telling that Beckett’s great collaborator, Billie Whitelaw, spoke of finding Rockaby ‘very frightening to do. And…desperately lonely to do’. In this work Beckett has recreated, without ever using the words, the universal and unyielding march of time, which must, inexorably, lead to death. The actor is alone and powerless and knowing all moments move towards the final moment when the chair will stop rocking and they won’t be called upon to join with the pre-recorded voice to plaintively cry ‘more’. With the meticulously written script prescribing each action of the actor there is very little for the actor to do and it is hard not to imagine, as the performance continues, an unseen struggle within the actor about mortality, a rising panic, and a desperation to share with the character the crying of ‘more’.

<<Continue to full review of Happy Days and Not I / Footfalls / Rockaby>>